Hyde Park Stories: Harold Washington Park

By Patricia L. Morse

The park that’s east of Hyde Park Boulevard between 53rd and 51st Streets is quietly tucked next to Jean Baptiste Point DuSable Lake Shore Drive, but there’ve been times when it’s been jumping with activity.

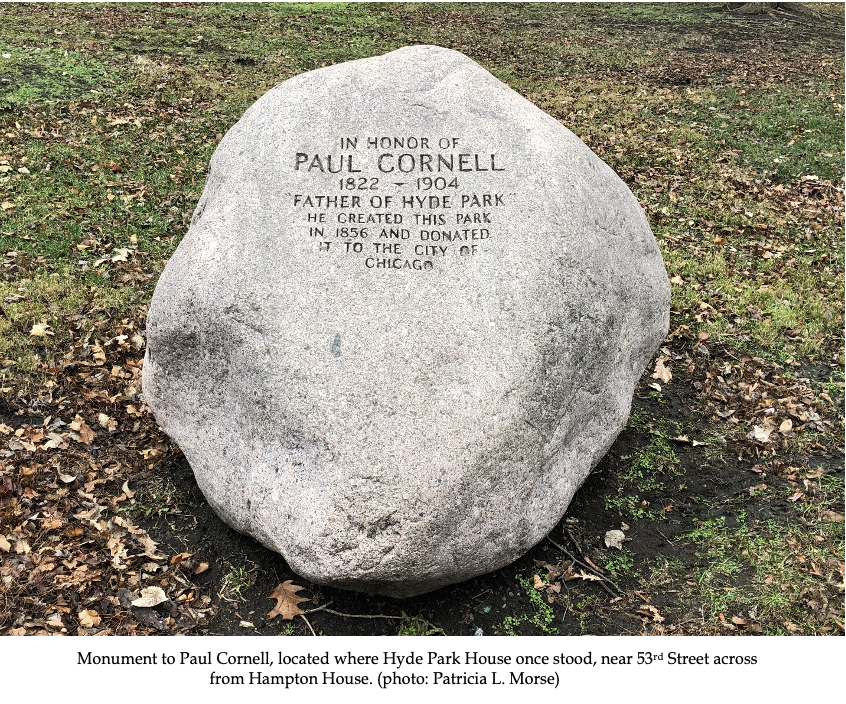

This park is where Hyde Park started. It’s close to where Nathan Watson once had a tavern along what had once been the trail between Potawatomi villages. It’s where Paul Cornell opened his train station and hotel, the anchors for his vision for Hyde Park. A rock in the park across from Hampton House marks the approximate location where the hotel stood from 1858 to 1877 on what was then the shore. If, in 1858, you stood where the corner of 53rd and South Shore is now, your feet would be wet. A breakwater ran north from the corner, forming a harbor. Half of the current park was under water.

Cornell landscaped the hotel’s grounds. They were so popular that excursion trains brought people from the city to, as the Chicago Tribune said, stroll along the beach of “fine sand” and under a grove of “old oaks that for ages have stood sentinels on the lake shore,” listening to the “soothing music of the waves.” In the winter, the park offered a seven-acre skating pond. In the summer, music festivals filled the grove, lit by Japanese lanterns. One festival featured the Chicago Light Artillery demonstrating its firepower, including a nighttime display of Greek Fire aimed at targets in the lake. In July 1872, the park hosted a free concert of French music. With the city in ruins from the Great Fire, thousands came to the park for the celebration.

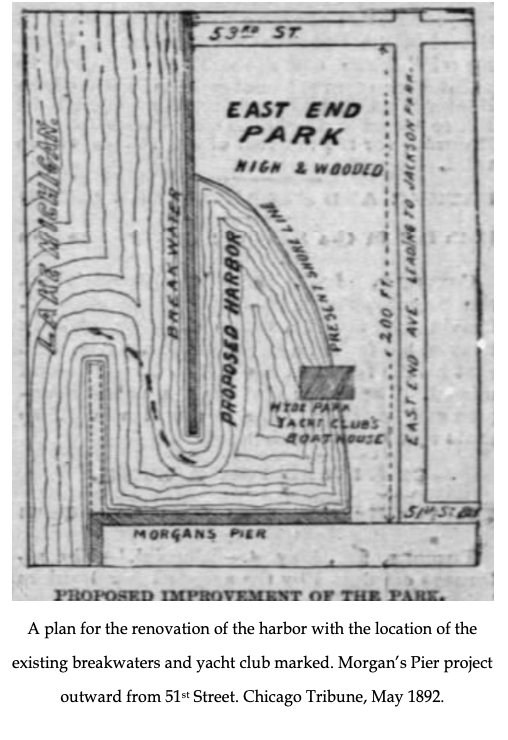

When the hotel burned in 1877, Cornell sold the lot and donated the rest to Hyde Park Township to form East End Park. Notoriously, the hotel ruins lay on the lot for decades. The Hyde Park Yacht Club built a “quite pretentious” boathouse by the water, until sand silted in behind the breakwater. In 1892, they argued that the city should pay for removing the sand to create a harbor for private yachts that would be convenient to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. The city, which had recently annexed Hyde Park Township, was somewhat surprised to learn it had a park. It even had a bank account of $8,500. The city quickly assigned control of the park to the South Parks Commission, though the city owned it.

As part of the harbor restoration, the city council proposed a naval academy in the park. The Pennsylvania Building in the 1893 expostion would move to East End Park after the fair to serve as the academy, but the plan fell apart. Having failed to convince the city to dredge the harbor, the yacht club sold its building and reorganized in Jackson Park Harbor.

The shallow sandy beach left behind the breakwater was beloved by neighborhood children even though there was a literal dump in the park with what the Tribune called “great heaps of variegated rubbish.” Hopefully there wasn’t much broken glass because enthusiasts taking the Kniepp Cure for rheumatism met in the park every dawn to stroll barefoot in the dewy grass.

By 1906, landscape architect Jens Jensen called the park a badly neglected jewel. He removed the rubbish and laid out new trees, walks, and benches. The 1908 Tribune praised the transformation “from a vacant lot into one of the most beautiful small parks in the city.” There were plans for a concrete beach “like Lincoln Park,” but those were scuttled when a storm ripped out the old breakwater and carried the beach away. Jensen made sure that the newly landscaped park was maintained.

The shallow sandy beach left behind the breakwater was beloved by neighborhood children even though there was a literal dump in the park with what the Tribune called “great heaps of variegated rubbish.” Hopefully there wasn’t much broken glass because enthusiasts taking the Kniepp Cure for rheumatism met in the park every dawn to stroll barefoot in the dewy grass.

By 1906, landscape architect Jens Jensen called the park a badly neglected jewel. He removed the rubbish and laid out new trees, walks, and benches. The 1908 Tribune praised the transformation “from a vacant lot into one of the most beautiful small parks in the city.” There were plans for a concrete beach “like Lincoln Park,” but those were scuttled when a storm ripped out the old breakwater and carried the beach away. Jensen made sure that the newly landscaped park was maintained.

In 1915, Harold Sisson began buying up the houses that once fronted the park and built six luxury apartment buildings. A few years later, he built the Sisson Hotel (now known as the Hampton House) near the original site of Paul Cornell’s Hyde Park House. Soon the park had four luxury hotels lining the park. They weren’t just bragging about their exclusive clientele. In 1925, millions of dollars worth of jewels were stolen from a South Shore banker’s wife in the East End Park Hotel.

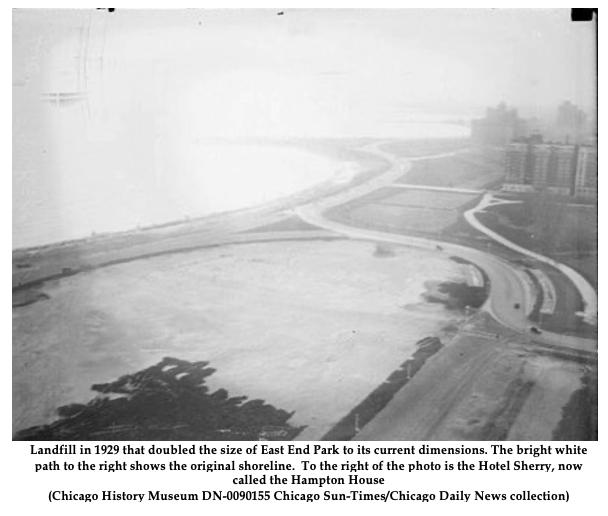

The hotel ads bragged about their park setting even as landfill started cutting East End Park off from the lake. The South Park Commission was creating a new lakefront highway to connect Jackson and Grant Parks. The music of the waves became the roar of traffic, but at least the project added five acres to the park itself, doubling it to its current size. By 1931, the new design included three features that are still in the park—the ever-popular tennis courts, the comfort station, and the model yacht basin. In 1931, 300 spectators watched a tennis competition on the courts. With Lake Shore Drive cutting the park off from the lake and more landfill east of the drive, a movement grew to rename the park after Paul Cornell. Habit as strong, however, and it stayed East End Park though it was no longer the east end of Hyde Park.

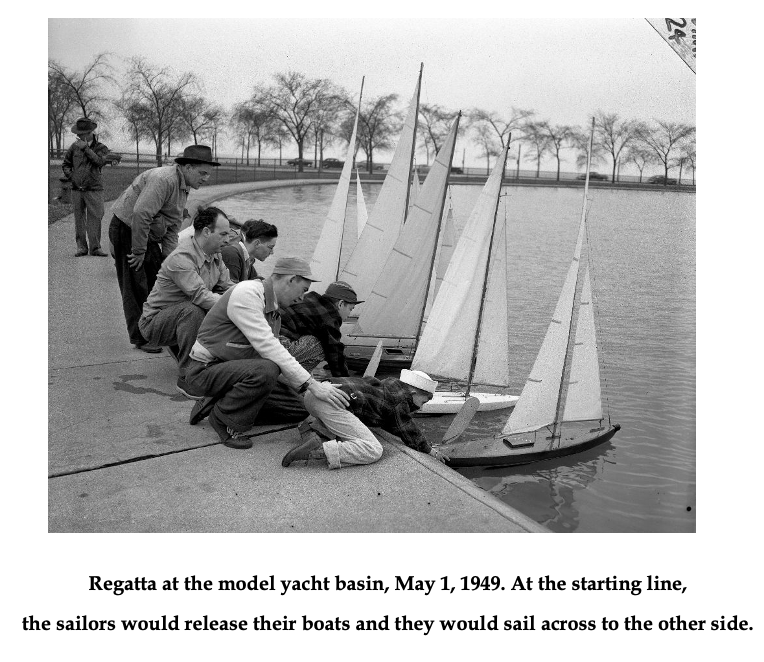

Chicago, busy planning the 1933-1934 Century of Progress, knew model yachting was an international sport and thought a competition-level basin would attract visitors. It invested in a 440 foot long, 305 foot wide, and 3 foot deep concrete basin so that it could host Model Yacht Days during the fair. The basin was carefully aligned with the prevailing southwest/northeast wind for optimum sailing and located just a few miles south of the fairgrounds, near hotels.

Model yachts were not child’s play. They were handcrafted, with vanes connected to the keels so they could go with or against the wind, propelled only by their billowing white sails. Competition boats were large—around 50 inches long. For years, the Midwest championships brought over 2500 people to the park several times a year. For decades, model yacht clubs came to the park every weekend to compete for prizes. It wasn’t just the middle-aged, middle-class White men in clubs who used the basin. The Park District taught yacht building—and the math and technical knowledge it required—in fieldhouses across the city. They brought the children and their boats to the park for regattas.

For quite a few years, a mystery sat next to the model yacht basin—a full-scale yacht in dry dock behind chain link fence. It was the “Dal.” Two intrepid sailors had crossed the Atlantic from Danzig, Poland, in it for the 1933-1934 World’s Fair. For 30 years it hung around the southside as people forgot what it stood for. In the 1960s, after the memoir of one of the sailors was republished, Poland reclaimed it and it sailed back across the Atlantic.

After World War II, the Drive expanded again, grabbing park land to wrap its lanes around both sides of the basin. Yachters accessed the basin through an underpass. Model yachts were promoted as a great father-son activity, but the clubs were slowly fading.

Then, in the late 1950s, Mayor Richard J. Daley proposed wiping out East End Park with a new expressway. The neighborhood protested, and the eight lanes of the expanded drive were built on new land east of the park. The basin was no longer surrounded, but fewer and fewer people came to the park to sail boats. The basin became home to ducks when there was water and dogs when there was none. For a long time, the park was an afterthought as part of Burnham Park, which stretched from 12th Street to 56th Street east of Lake Shore Drive.

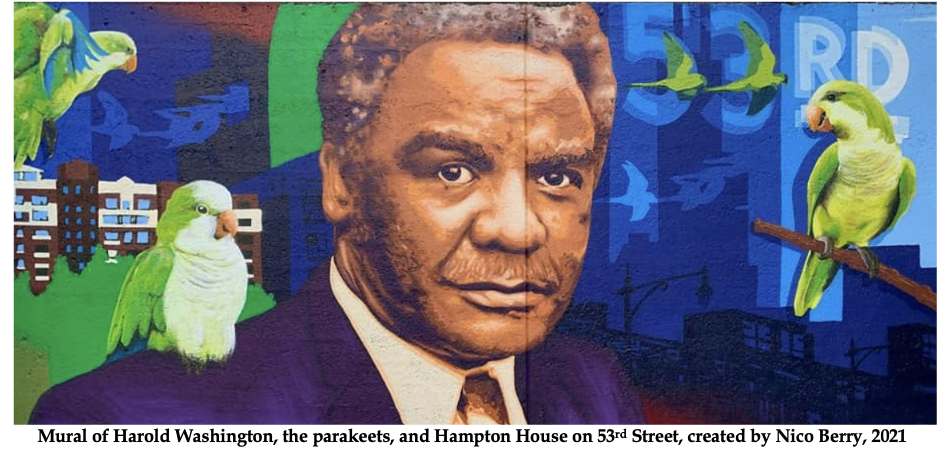

The park was fairly quiet until 1980 when a new noise disturbed the peace—the squawking of very large, very green Monk Parakeets. Their nest was in an ash tree near the Paul Cornell boulder. Luckily for the visitors seeking them, it didn’t take much skill to spot the dozens of bright green heads poking out of the many chambers in the 10-foot wide sphere of sticks. The parakeets became the mascots of Mayor Harold Washington, who lived across the street at Hampton House. The parakeets lived there until 2004, when the weight of the massive nest suddenly split the ash tree in two. Tree and nest crashed to the ground in ruins. The parakeets fled despite the valiant efforts of volunteers to save the nestlings.

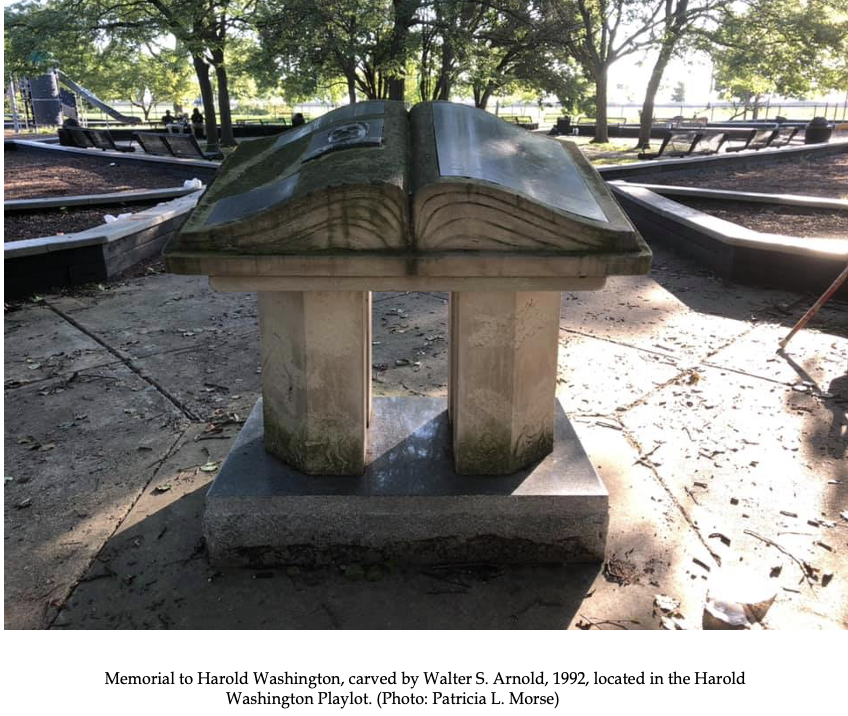

In 1987, Harold Washington died suddenly, right after his triumphant re-election. To the city, he was the first African-American mayor of Chicago and the man who fought political corruption. The citywide memorials—the central library and community college—reflect his love of books, faith in education, and belief that “the guiding principle of government is to do the greatest good.” To Hyde Park, Harold was the neighbor who had long represented its concerns in Springfield, Washington, and city hall. He was a familiar presence, browsing the bookstores late at night or holding court in the restaurants. Many Hyde Parkers were passionately committed to his campaigns. The neighborhood needed its own memorial. The committee considered converting the yacht basin into a memorial. Portrait busts of him at different ages around the water would celebrate his long rise on the southside. It didn’t happen, but, in 1992, donors did rename the playlot after him and place a stone book in his memory there. The park as a whole was separated from Burnham Park and renamed.

Then, in 2007, a coalition of politicians and donors decided that the park should be a gateway to Hyde Park, welcoming motorists to pull off the drive. The basin was refurbished, the fountain was rebuilt, and Hyde Park resident Virginio Ferrari’s statue “Ecstasy or Due amanti che guardano le stelle” was installed. At its dedication, it was called “a celebration of life,” as, indeed, the park itself has long been.

Please note: A shorter version of this story originally appeared in the Hyde Park Herald. This is an expanded version which includes more photos.

Sources:

The Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Inter-Ocean

The Surbanite Economist

The Hyde Park Herald .

The National Hotel Reporter

https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/washington-harold-park

New Life of the Yacht "Dal" - News - Archive - National Maritime Museum in Gdańsk (nmm.pl)