Hyde Park Stories: The David Wallach Fountain

The David Wallach Fountain by Patricia L. Morse, July 2022

David Wallach Fountain (Photo by Patricia L. Morse)

Thousands of Hyde Parkers have walked by the David Wallach Fountain on Promontory Point, but few have known about its donor, David Wallach.

David Wallach was born in Germany in 1832. After immigrating to the United States and a brief stay working with his brother in Rockford, Iowa, he moved to Chicago and became a partner in the firm of Cahn, Wampole & Co., wholesale clothing manufacturers. After his retirement in 1891, he dabbled in photographic supplies until his death in 1894. The Cook County Death Index called him a “capitalist.” To the census, David Wallach said he was a “wholesale clothing merchant,” but I think the label I would use is “philanthropist.” The Chicago Chronicle said that, in spite of his wish for anonymity, the board of every charity in the city knew him and knew that, if they reached out, it was never in vain. He was, unsurprisingly, a member of Chicago Sinai Congregation, whose widely influential rabbi, Emil G. Hirsch, inspired his congregation to address the social ills of the day.

Wallach’s will made some of his private philanthropy public. Among the many bequests were ones to Michael Reese Hospital, the Institute for Crippled and Destitute Children, and a number of Jewish charities. About 10% of his substantial estate went to the Chicago Orphan Asylum, which he’d been supporting. Smallpox and cholera orphaned a large number of children throughout the 19th century so the need was great and on-going. Wallach knew covering the basics wasn’t enough. His friend, Dr. Edmund J. Doering, recalled going with Wallach to the asylum, bringing treats because the children needed some joy. Doering wanted the children to remember “their staunchest supporter” so endowed an annual joyful “David Wallach Day,” on November 3, Wallach’s birthday. It brought puppet shows, magicians, ice cream, and cake for the 200 orphans. But as so often happens, the day was soon forgotten.

At the reading of Wallach’s will, there was one donation that caught the Tribune reporter’s eye. Upon his wife’s death, $5000 was set aside “for the purpose of erecting a fountain in the city of Chicago for the free use of both men and beasts” at a location south of 22nd Street, north of 33rd Street, and east of Michigan Avenue—that is, near Wallach’s home at 3332 S. Vernon—a gift to the working horses of his neighborhood. The money did go to the city but no fountain appeared.

In 1914, his sister wrote the mayor of Chicago for an explanation. The city scrambled to unearth the will. Alderman George F. Harding, Jr. (the Harding who had a museum and whose medieval armor is still on view at the Art Institute) was delighted because his brother had gone to school with Wallach’s son. He knew the perfect spot in his ward—where 35th Street, Vincennes, and Cottage Grove came together. And yet, nothing happened.

In 1937, David Wallach’s heirs brought it up again. Lawsuits ensued. Once the dust settled, the heirs had two conditions. Any leftover funds had to go to the Chicago Orphan Asylum, and they wanted David’s name on the fountain.

Wallach’s heirs were living in the Parkshore residential hotel on 55th Street near South Shore Drive. They had watched Alfred Caldwell landscaping Promontory Point next door and thought that would be an ideal location for the fountain. Apparently the only ones who didn’t think it was ideal were the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars, who sued to have it on 47th Street. The judge told them that the will specified 55th Street and the Lake, which, of course, it didn’t.

Meanwhile, there was a design competition, which Frederick C. Hibbard (1881-1950) and his wife, Elizabeth Haseltine (1894-1950), won. They lived at 1201 East 60th Street as part of Lorado Taft’s Midway Studios. Hibbard designed the base in what the Tribune called “the modern style” using Dakota Mahogany granite, which is hard rock billions of years old. The polish protects it from the weather. It’s a monument that should last.

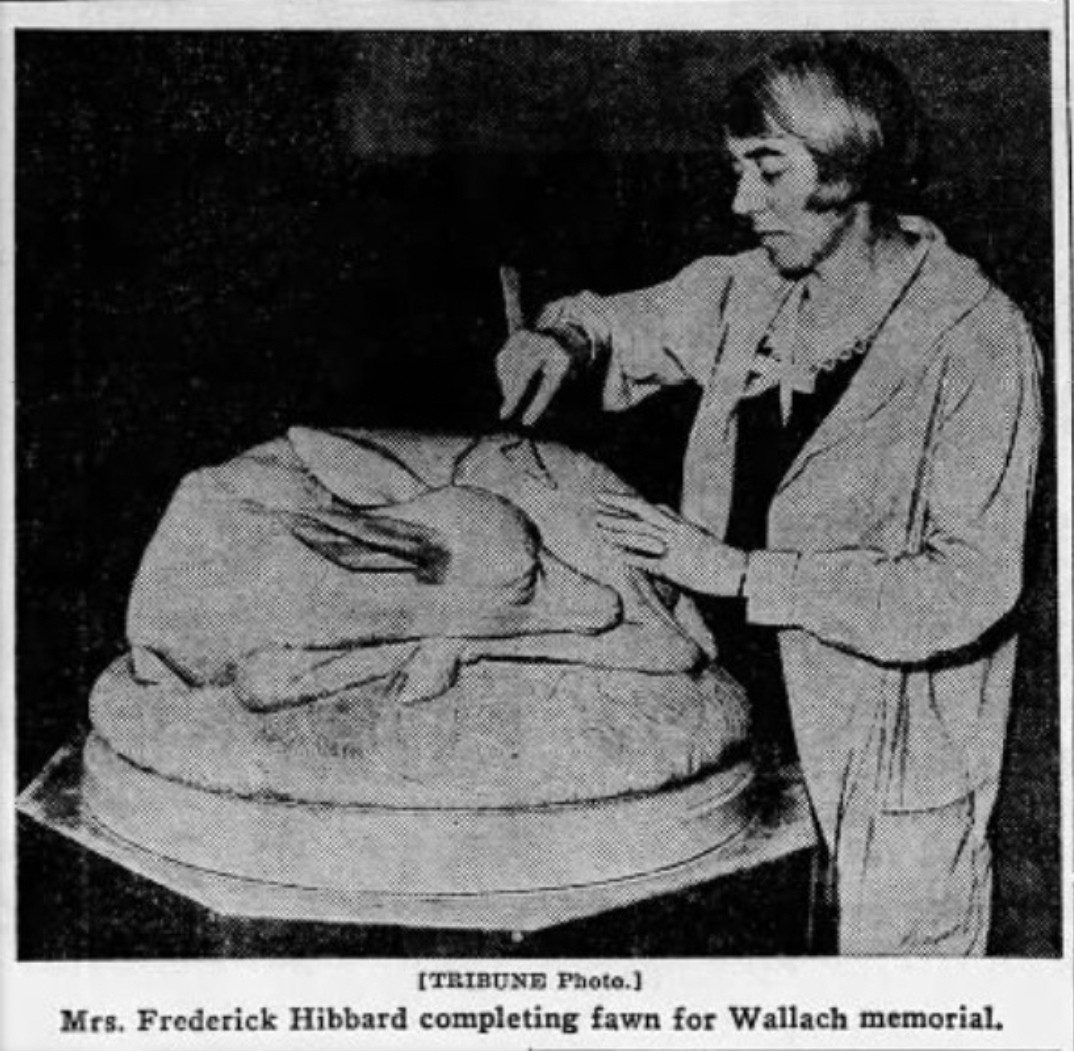

Elizabeth Haseltine, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, designed my favorite part, the sleeping fawn. Haseltine was an assistant professor at the University of Chicago and assistant to Lorado Taft. She was renowned for a Baby Pegasus sculpture, which she exhibited several times at the Art Institute. The Tribune art critic called her work “delicate, true, simple, and fascinating.”

I suspect Baby Pegasus would have delighted Wallach, but Haseltine wanted something naturalistic to match Caldwell’s landscape. She modeled her statue after a sleeping fawn she saw in the Lincoln Park Zoo. She specialized in animal sculptures and had three in the brand-new Japanese stroll garden on Wooded Island: a squirrel, a kingfisher, and a great blue heron, all carved out of tulipwood and located near the waterfall.

The fawn had adventures later in life when in 1981, a dog walker reported it stolen. Two weeks later an alert Hyde Parker spotted it in a salvage warehouse where it had been fenced for a mere $150. The episode exposed the Park District neglect of the Point because the Park District supervisor whose office was in the fieldhouse hadn’t realized it was missing though it had been gone for two weeks. He also hadn’t noticed that someone had taken an axe to the wooden benches at the Point. As the Herald said, the patronage-ridden bureaucracy of the Parks could care less about a "small charming beloved landmark in a small charming beloved South Side park" and so the citizens organized the Friends of the Point.

Though there were horses on the bridle path in Jackson Park, the committee in charge apparently thought horses wouldn’t go through the underpass to the Point. To accommodate the will’s instruction that it serve “man and beast,“ the fountain has a low basin for dogs and birds. The Tribune snarked that you could lead a horse to this fountain, but there was nowhere for a horse to drink—but in fact I’ve seen horses manage to drink from it. The three drinking fountains around the edge are low enough for children. I think David Wallach would have liked that.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in the Hyde Park Herald, September 20, 2021. Hyde Park Stories: The David Wallach Fountain | Local News | hpherald.com

For more information about David Wallach and the fountain, see “Welcome to the Point: The David Wallach Fountain,” in the Autumn 2019 issue of Hyde Park History.

1955 photo by Mildred LaDue Mead. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf2-09143], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.)