Hyde Park Stories: SPIA Horse Water Bowl

Written by Patricia L. Morse

Near the southeast corner of 57th and Kimbark, a granite bowl displays the initials “SPIA,” which stand for the “South Park Improvement Association.” The 1905 bowl watered horses, but what was the SPIA?

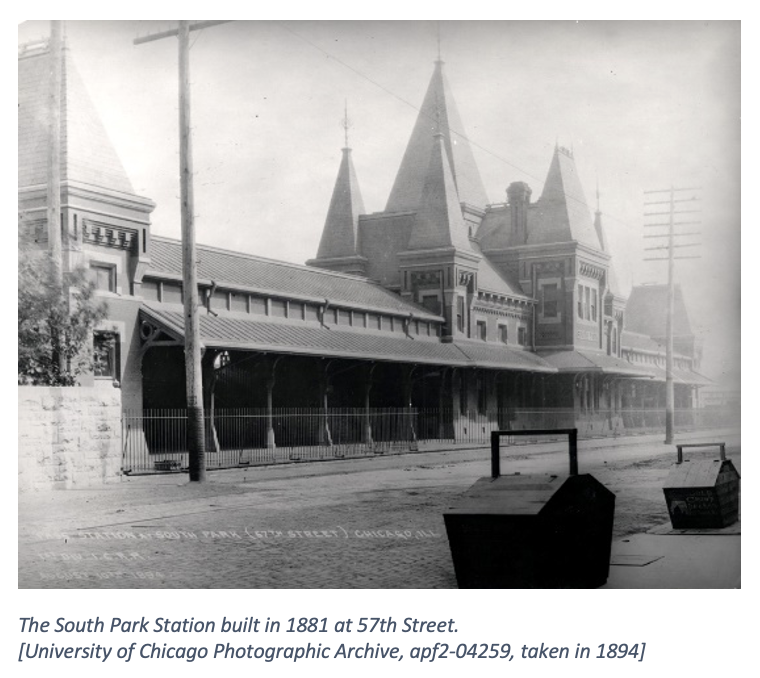

“South Park” once referred to the neighborhood that formed around the train station at 57th Street. The railroad called the stop “Wood Pile” because it was where the steam engines refueled. After real estate investors complained that they couldn’t sell lots in Wood Pile, the Illinois Central renamed the stop “Woodville” and then “South Park” in 1881 because it was near the newly landscaped north end of Jackson Park, which was the eastern part of the South Parks System (Washington Park, the Midway, and the boulevards). Upper-middle-class professionals quickly moved in.

A trolley on 55th Street created a commercial strip and a northern border. On the east, livery stables, taverns, and cheap housing sprouted up along the tracks on Lake Park. The Midway Plaisance defined the southern border. On the west, a stream meandered southeast from property owned by Marshall Field, who shrewdly donated 10 acres to the University of Chicago in 1890. When the university realized it needed more land, Marshall Field charged them a fortune. When the university lured faculty to Chicago, Field made a second fortune selling lots east of campus. Eventually 44 professors built homes in South Park.

Meanwhile, the 1893 World’s Fair replaced some of the low frame buildings with multi-story hotels. The Fair also inspired the City Beautiful movement and the belief that clean, landscaped cities produced physical, mental, and moral health. The formidable Chicago Woman’s Club embraced the cause across the city.

In 1901, two members of the club, Mrs. Frank Asbury Johnson (Annie) and Mrs. Joseph Twyman (Caroline), met in Annie Johnson’s house (5817 S. Kenwood) and decided they needed a South Park Improvement Association. When they called a public meeting of South Park residents, the Inter Ocean newspaper snarked that “women accustomed to Persian rugs and polished floors” were going to clean the streets, though it conceded that they weren’t going to do it themselves in their “dainty shoes” and “trailing skirts,” which was particularly unfair to Annie Johnson, who crusaded for women’s dress reform, including eliminating “trailing skirts.”

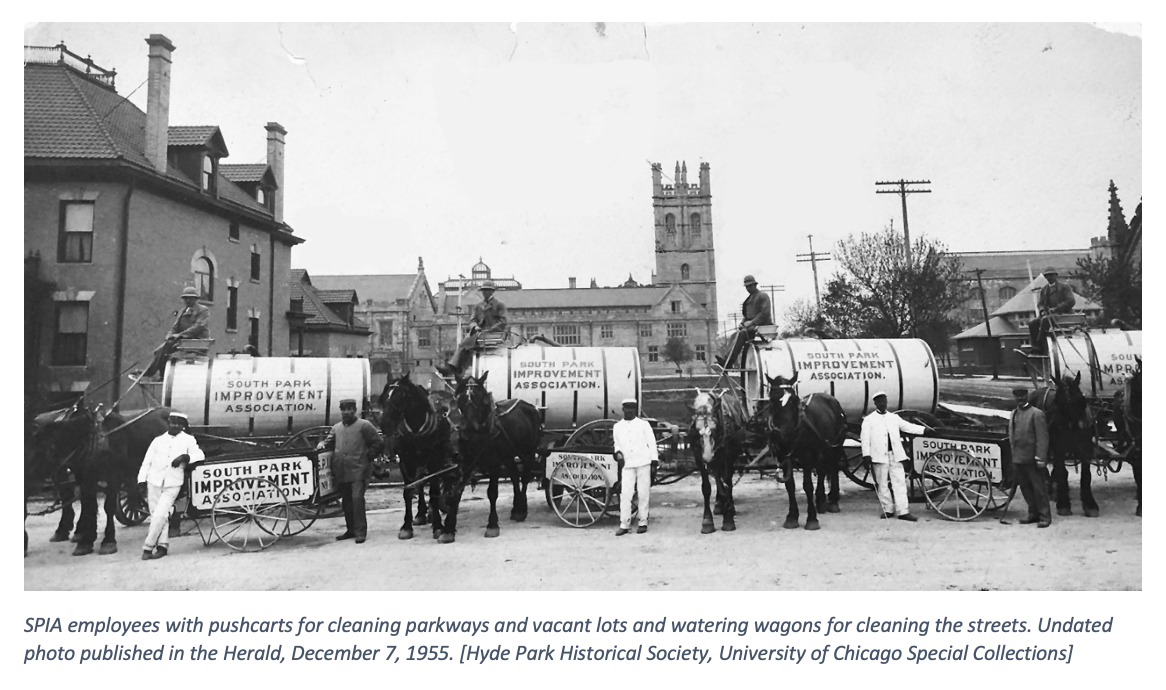

At the meeting, Annie Johnson and Caroline Twyman made their case. The streets and alleys, which were unpaved with few gutters or sewers, needed watering down to prevent great clouds of manure-laden dust being kicked up by wagons and horses. Litter and leaves needed to be cleared from the sewer inlets on the paved streets. Snow needed to be cleared from sidewalks. Vacant lots needed to be picked up and weeded. Ordinances needed to be enforced in the firetrap buildings the fair left behind. Half the district had no alleys, so garbage and ash cans from coal-burning furnaces blocked sidewalks, waiting for the city scavenger. Black coal smoke billowed from large polluters like the University of Chicago. The raw new buildings throughout the neighborhood had no landscaping. The streets had no shade. The neighbors agreed. They elected an almost all-male board of volunteers to incorporate the SPIA as a not for profit to collect dues and hire a superintendent and workers, primarily from the working-class area along Lake Park where there were stables.

With the SPIA a success, Annie Johnson left to organize a federation of improvement clubs across the city and join the Chicago Woman’s Club Outdoor Art League. Caroline Twyman (5759 S. Dorchester) stayed on as secretary for a few years. Her husband, Joseph Twyman, was the interior decorator for the Tobey Furniture Company of Chicago, which specialized in handmade Arts and Crafts furniture. Twyman had connections with the British Pre-Raphaelites and brought the two Edward Burne-Jones stained glass windows to the Second Presbyterian Church at 1936 S. Michigan. More importantly, Twyman brought the philosophy and art of William Morris to America. Twyman embraced William Morris’s belief in arts and crafts as a radical resistance to the industrial age. The SPIA inspired him to launch the South Park Workshop (5835 S. Kimbark) in 1903. The workshop housed artisans and taught bookbinding, weaving, metal work, pottery, and furniture. He wanted to create an artists’ community that would accomplish for the home what the SPIA was accomplishing for the neighborhood.

Unfortunately, Joseph died in 1904. The workshop mounted an exhibit in the Del Prado Hotel after his death, but it didn’t last long without him. His vision of an artists’ colony, however, did live on. Radicals and artists thrived in the cheap housing left by the Fair. One branch of the colony occupied a cluster of buildings on Kenwood one block north of the workshop. I like to think of them all—the artists, the iconoclasts, the writers, the dancers in Katherine Dunham’s troupe—enjoying the shady streets brought to them by the SPIA and Mrs. Herman J. Hall of 5545 S. Blackstone.

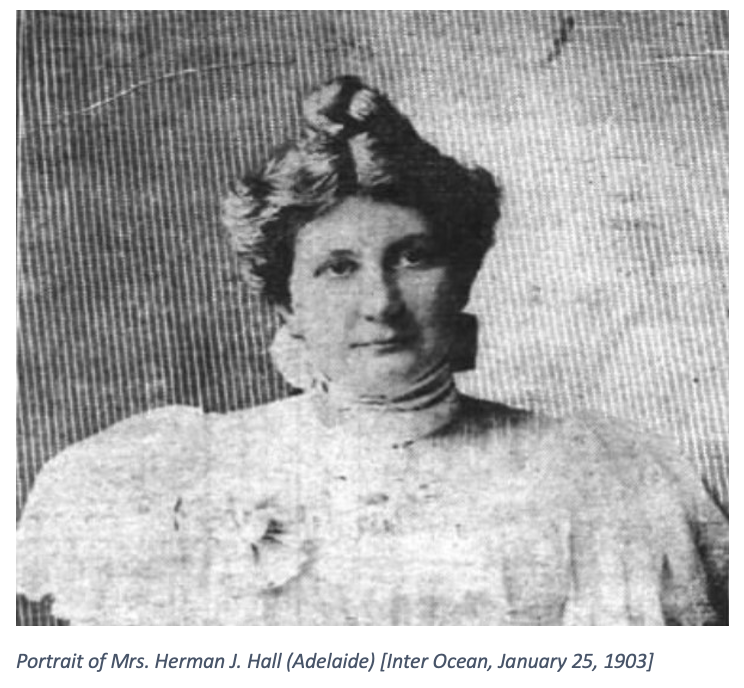

Adelaide Hall had strong opinions about many things. When it came to architecture, she was offended that many buildings cut corners by using limestone for the façade and Chicago common brick for the sides and backs. As she said, they were all “Queen Anne” in front and “Mary Anne” in the back. She made headlines when she scolded an SPIA meeting, telling them they needed “verdure” to cover up their ugly raw edges. The Inter Ocean noted that “owners of $500,000 cottages sat in amazement as they heard their palaces spoken of as architectural freaks.” She went on to tackle public art. She became a power in the National Outdoor Art League. She thought the boring granite effigies of famous men made parks look like cemetaries. As she told one convention, if the statues had to be in parks, “it would be wise to conceal them in thickets, where those who wished to find them might do so, but where there would be no danger of other visitors coming upon them unawares.”

Adelaide Hall was a passionate believer in the City Beautiful. She was personally offended by all the raw new buildings without “verdure.” She had a vision of the South Park neighborhood as a unified, parklike landscape. In 1901 she started working with Jens Jensen, landscape architect, as the judges for the City Beautiful contests sponsored by the Tribune. With his help and that of the botanist at the Field Columbian Museum, she produced plans for the parkways. The SPIA planted hundreds of trees and landscaped the vacant lots and railroad embankment. Adelaide Hall also issued pamphlets to instruct the home gardeners of South Park on adding flowers, shrubs, and trees to their raw lots.

In 1903, the Tribune ran a mocking the idea of club women trying to improve the neighborhood—going on at great detail about how the lady sparrows were forming an association to improve things and dragging their husband sparrows in on the effort. But even the Tribune noted that the landscaped empty lots were “now the home of the butterfly and the bee.” If the author had waited another year, he could have included the sparrow fledglings because the SPIA soon began to offer prizes to the child who planted the most parkway trees.

The SPIA pushed to get paved streets, sewers, and streetlights and nudged owners to keep up their property, but mostly it focused on the basics of trash, streets, snow, and trees. It was such a success that they were periodically pressured to expand their territory, but they said no. Though individuals might be sympathetic, the SPIA resisted the frequent pressure to take on other crusades, like the Hyde Park Protective League’s crusade against drinking, gambling, and crime along Lake Park. In the 1930s, the university wanted the SPIA to police the liquor laws, report zoning and ordinance violations, and prevent “undesirables” from moving in. They ignored the university. In the 1940s, real estate interests pressured the SPIA to promote restrictive covenants. The SPIA said no.

A small quirk in the SPIA affairs was the repeated difficulty in getting the city council to agree to let them use city water to wash the streets. The council wasn’t against clean streets. The machine liked to use the request to punish Hyde Park’s rogue aldermen. Charles Merriam, Paul Douglas, and Leon DesPres all had a fight to get approval for the SPIA.

It was urban renewal that did in the SPIA. Aside from filling South Park with rubble, torn down buildings paid no membership dues. Too often the new residents of the townhouses saw no need to support community-wide services. The SPIA brochures of the 1960s pleaded, “We are all part of the same community!” But too few were convinced enough to pay dues. The SPIA was absorbed by the South East Chicago Commission in 1974 and the services ended.

In 1979, Mrs. E. Hector Coates of 1220 East 57th Street, a long-term resident who fittingly believed in gardening to beautify the neighborhood, found the SPIA horse bowl in an alley. At the time, Dev Bowley was part of the Hyde Park Historical Society. He remembered the SPIA well. He set up the bowl in front of the bookstore he owned—now 57th Street Books—which was also near Mrs. Coates’ house. It’s a memorial to the City Beautiful.

A shorter version of this story appeared in the Hyde Park Herald, April 12, 2022 Hyde Park Stories: SPIA water bowl | Local News | hpherald.com

Sources:

Archives of the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Inter Ocean, and the Hyde Park Herald

Special Collections at the University of Chicago